The Mysteries of Mount Shasta

The guys at San Jose Hood Cleaning felt that this was an article worth resurrecting. So they asked that we relaunch this so that others may enjoy it.

Mount Shasta is a keeper of secrets. Prone to violent outbursts over the eons, this volcanic massif has sat relatively silent for hundreds of years. But the same cannot be said of the mountain’s worldly visitors; they have spilled many of their secrets. The least well-kept of these secrets is that Shasta harbors all-time classic ski descents. What makes a ski descent an all-time classic? I’m not sure who maintains the standards for these things, but perfect springtime corn snow and 7,000+ feet of skiable vertical on a 14,000+ foot volcano probably has something to do with it.

Also, no secret is the mountain’s namesake, the Shasta Indians, who were among the first to lay any spiritual claim to the place. They believed the mountain stood at the dawn of time at the center of creation. This too ranks poorly kept secret, if only because it’s a little obvious. Wouldn’t you be more surprised if this massive monolith wasn’t formed by the Great Spirit pushing ice and snow through a hole in heaven to create a stepping stone down to this world? Native American creation mythology has always featured the natural forces of this world, and Mount Shasta is undoubtedly the most likely culprit within the eye-shot of the numerous tribes in the neighborhood. Where else could it serve as the fountain of creation and the home of the Great Spirit? This mountain, like so many of the Cascade volcanoes, stands alone.

Perhaps one of Shasta’s best-kept secrets, one of the things you might not divine simply driving by on I-5, is that the mountain is not just the center of creation and the spiritual universe; it also hosts the underground city of a super-race of intelligent beings, refugees from their lost civilization on a sunken continent in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. “Oh, really,” I hear you wonder disdainfully. Well, apparently, yes. Follow me, your Mountain Spirit Guide, as I shine a light on the supernatural and unravel… the mysteries of Mount Shasta.

It was an early May morning as I sat in the Black Bear Diner in the town of Mount Shasta, about to enjoy a gut-bomb of a Denver omelette before our climb. On the way in I happened to pick up a copy of the Mountain Spirit Chronicles, eager to learn more about the forces at work in the town of Mount Shasta itself. The Black Bear is a cute little franchise; the diner brims with tchotchkes, trinkets, knickknacks, and every type of downhome kitsch imaginable. You know the type.

But situated in the decidedly offbeat town of Mount Shasta, it is a place where classic Americana breeds with the occult, where waiters and waitresses alike might sport pink hair in polka dot bonnets, nose piercings, neck tattoos, not to mention Santa Claus suspenders in the middle of May. I once asked someone from the town of Mount Shasta what it was like to grow up there. “Let me put it this way,” he said, “There are more crystal shops than bars.”

Mount Shasta is a focal point of New Age spirituality. Over a hundred different groups (and by “groups”, I mean sects… and by “sects”, I mean cults) hold the mountain in particular sacred prominence. The mountain has been identified as a cosmic power point, a UFO landing spot, the entry point into the fifth dimension (a place characterized by “playful tenderness”, according to the paper I had just picked up), a source of magic crystals, and one of the Seven Sacred Mountains of the World.

Sipping black coffee, I thumbed through the Mountain Spirit Chronicles with my friend, Chrix. The publication is produced by the proprietor of a local tour company, Shasta Vortex Adventures. This woman, Ashalyn, has the rather unique ability to channel the thoughts and words of otherworldly beings. The lede of her first article starts “I, Thoth the Atlantean, have been around for many unusual happenings, having to do with this planet.” Chrix and I read on, enthralled. “As we move into the actual time space of 2012, many people are in confusion.” We nodded in agreement.

We read about sacred site treks and guided vision quests with the giddy anticipation of starting on our own vision quest to the summit within the hour. To my surprise, I learned that the arrival of New Age worshipers has brought conflict to the mountain along with their crystals. As visitors, we are never as low-impact as we would like to think we are. Traditional native American sacred places on the mountain, such as prayer springs, have attracted crowds and suffer from a general lack of respect.

The Mountain Spirit Chronicles detailed an incident where a young man stood up from a group meditation near one prayer spring and started walking. He was barefoot, wearing only a robe, but his friends just watched as he followed his inner compass up the mountain on a once-in-a-lifetime vision quest. His body was recovered a couple of days later somewhere above 9,000 feet. With this somber turn of events, Ashalyn’s column continued with some helpful tips on backcountry safety: “Yes, I believe in miracles, but while you’re waiting for one to occur, you’ve got to remain safe and prepared for the existing conditions around you, if at all possible.”

Out the window of the diner, Shasta loomed inquisitively over our omelets and breakfast conversation. “They’re saying WHAT about me?!,” a voice seemed to bellow down the mountainside. Ashalyn’s articles continued on, extolling the virtues of the enlightening spiritual vortex surrounding Mount Shasta. “As a metaphysical healer, reader, channel, and teacher, I’ve learned to receive messages from a variety of sentient beings,” she claims, “the most recent being the sentience of a large root beer-colored Andara crystal.” If you are interested in intuitive awakening training, shamanic hypnotherapy sessions, or what any self-aware root beer crystal has to say, then Ashalyn is definitely your gal.

While the mountain is renowned for the peculiarities of New Age spirituality in general, it is the Lemurians to whom the mysteries of Mount Shasta owe most of their merit. The Lemurians, refugees from their sunken continent of Lemuria, are the contemporaries of other lost civilizations such as Atlantis, long since sent asunder by cataclysmic earthquakes or the disaster du jour. They now call Mount Shasta their spiritual and physical home. These Lemurians who live in California are aware of the fate of their ancestors, and each night at midnight they perform a ritual of thanksgiving and adoration to ‘Gautama’, the Lemurian name for America. But interestingly, the term “Lemuria” itself is not of Lemurian origin.

According to Bill Miesse, the author of Mount Shasta, An Annotated Bibliography, “mid-19th Century paleontologists coined the term ‘Lemuria’ to describe a hypothetical continent, bridging the Indian Ocean, which would have explained the migration of lemurs from Madagascar to India. Lemuria was a continent that submerged and was no longer to be seen. By the late 19th Century, theosophists had developed theories that the people of this lost continent were highly advanced beings. The location of the Lemurian folklore changed over time to include much of the Pacific Ocean. In the 1880s a Siskiyou County, California, resident named Frederick Spencer Oliver wrote A Dweller on Two Plants, or, the Dividing of the Way which described a secret city inside of Mount Shasta, and in passing mentioned Lemuria.”

And so the seed was planted. It has long since blossomed into many branches of belief regarding Mount Shasta’s significance in this world and beyond. Although any passing geologist could tell you the modern theory of plate tectonics has rendered the original concept of Lemuria obsolete, the dutiful folks running the crystal shops and vortex adventures tours would never let mere facts get in the way of a good story, or a paying customer. And neither would I, for that matter. But why is the legend so prominent? Why is there so much conviction in the existence of Lemurians?

Reported personal encounters on higher elevations of the mountain have lent much credence to the legend. Numerous unconfirmed telescope sightings of Lemurian temples and villages sculpted from marble, onyx, and gold have been attributed to professors and scientists throughout the 1920′s and 1930′s, including Edgar Lucian Larkin who ran the nearby Mount Lowe Observatory. These observations helped spark interest and fascination in the Lemurians. Another noteworthy source, Dr. M. Doreal, describes his visit to a Lemurian city within the mountain in 1931, “….the space we came into was about two miles in height and about twenty miles long and fifteen miles wide and it was as light as a bright summer day, because suspended, almost in the center of that great cavern of space was a giant glowing mass of light.”

In 1932, the Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine sent journalist Edward Lanser to get the scoop. From the observation car of his train, he saw at sunrise that the “whole southern side of the mountain was ablaze with a strange reddish-green light.” Later, he asked a conductor about the phenomenon. “‘Lemurians’, he said. ‘They hold ceremonials up there.’” Lanser continued, “I motored toward the point of my investigation, pausing at Weed, a town near Mt. Shasta, for the night. In Weed, I discovered that the existence of a ‘mystic village’ on Mt. Shasta was an accepted fact. Businessmen, amateur explorers, officials, and ranchers in the country surrounding Shasta spoke freely of the Lemurian community, and all attested to the weird rituals that are performed on the mountainside at sunset, midnight, and sunrise.”

Lanser describes the truth, as he saw it, “the Lemurians have been seen on various occasions; they have been encountered in the Shasta forest, but only for a brief glimpse, for they possess the uncanny secret knowledge of the Tibetan masters and, if they desire, can blend themselves into their surroundings and vanish.”

“At times they came into the neighboring towns–tall, barefoot, noble-looking men, with close-cropped hair, dressed in spotless white robes that resemble in style the enveloping garment worn by the high-caste East Indian women today–to patronize certain stores…..Various merchants in the vicinity of Shasta report that these white-robed men occasionally come to their stores. Their purchases are of a peculiar nature. They have bought enormous quantities of sulfur as well as a great deal of salt. They buy lard in bulk quantities, for which they bring their own containers and peculiar transparent bladders. The gay materials and novelties of our modern civilization do not attract these simple people at all. Their purchases are always paid for with gold nuggets… They have frequently donated their large gold nuggets to charity. During the World War, they came forward with generous gifts to the American Red Cross, and more recently they sent a bag of gold to the fund for sufferers of the Japanese earthquake…”

Personally, I find it very reassuring to know that in addition to possessing extra-sensory perception, harnessing atomic energy, and constructing giant airships as long as 18,000 years ago, the Lemurians are also good-hearted philanthropists.

As a matter of fact, I had my own serendipitous encounter on the summit pinnacle of Mount Shasta last year. Frankly, I was not looking for Lemurians, I was looking to make some turns. It was mid-June and the conditions had not been particularly cooperative. Like so many prominent mountains, Shasta seems to generate its own weather. When you consider this in the context of the Great Winter of 2011, you might begin to imagine the limited opportunities for skiing when even into June the mountain was bathed in gale-force winds, sub-zero temperatures, and blinding whiteouts.

At that time in my life, I was living out of a borrowed van between jobs. After spending a month and a half driving up and down the Eastern Sierra, getting a taste of what it was like to camp in blizzards, rappel into couloirs, bathe in hot springs, and fish the best spring creeks and tailwaters this side of the Sierras, my trip (which I shamefully never wrote about) culminated at Mount Shasta. And we had managed to arrive at the foot of the mountain just in time for low clouds and wind to obscure the very sight of it. We slogged up to high camp at Helen Lake with the clouds in our midst. But the next day we awoke at 4 am to sparkling skies and pushed to the summit, achieving our lofty goal of 14,179 feet. It was literally, if not figuratively, the highest I’ve ever been. And it was not more than forty steps down from the summit that I encountered Lonnie.

Chris and I had managed to reach the summit at a time of rare vacancy that weekend. We had the pinnacle to ourselves, admiring the view from what felt like the top of the world, but howling winds conspired to push us back down. It was clearly time to go. We had left our skis at the summit plateau, totally uninterested in skiing down the bulletproof ice necessary to claim descent from the true summit. Frankly, who cares about such masochistic technicalities when it cannot possibly add to the fun factor? This year, I saw someone do it: ski from the true summit, chattering down jagged ice, surely losing a few fillings along the way. “Hey, was that worth it?” somebody shouted. We all knew the answer. The skier only shook his head.

Chris started down on foot, back to our skis, while I savored the last of the view in solitude. I stared down at a helicopter, well beneath my feet, circling the mountain. Admiring the steep drop-offs down the barren eastern face, I retrained my eyes down the icy slope I had picked my way up. Inexplicably, I suddenly sensed the presence of a silhouette next to me. Turning back towards the sheer cliffs, a man with a wooden staff stood up in front of me. He had not been there only moments before. What route could he possibly have come up with? “I’m not really sure,” he stuttered. The cogs began to turn and I made the connection. Didn’t we overhear a climbing ranger talking to a woman at high camp who said her husband hadn’t returned yesterday after high winds and whiteout conditions swept across the summit? ”Yeah, she’s probably worried sick,” he groaned.

I helped the lost-and-found climber off the pinnacle down to the summit plateau. He was clearly delirious, walking slowly and without particular coordination, long since out of food and water. But he shared his name, Lonnie, and recounted his story. He had been climbing alone when vicious winds set in. In the thick of a whiteout at 14,000 feet, he was unable to identify any point of reference. Desperate to get out of the worsening weather and back to his wife, he wandered off the wrong side of the mountain. By the time he realized he had descended the opposite face, darkness was falling. He hunkered down in a snow depression, with nothing but the clothes on his back, and shivered through the night. He did not sleep a wink. When the sun rose over clear skies, he started climbing back up to the summit. That was when I found him, or should I say, he found me.

We sat down and shared our food and water with Lonnie as I tried to get in radio contact with some of our friends down the mountain. We had started that morning as party of six. Two others with skis had turned around halfway up from Helen Lake, and two others without that extra weight hustled up from Helen Lake and had already passed us on the way down. By the time we were sitting on the summit plateau with Lonnie, one pair of friends was back at Helen Lake and another pair was all the way back at Bunny Flat. I was able to radio both of them, and alert the rangers and search and rescue personnel stationed at Helen Lake and at Bunny Flat to our discovery. Immediately, one of the rangers was on the horn with Lonnie. ”Lonnie, are you hurt?” the ranger asked. Lonnie paused, seemingly bewildered, but then cracked a smile. “Only my pride.”

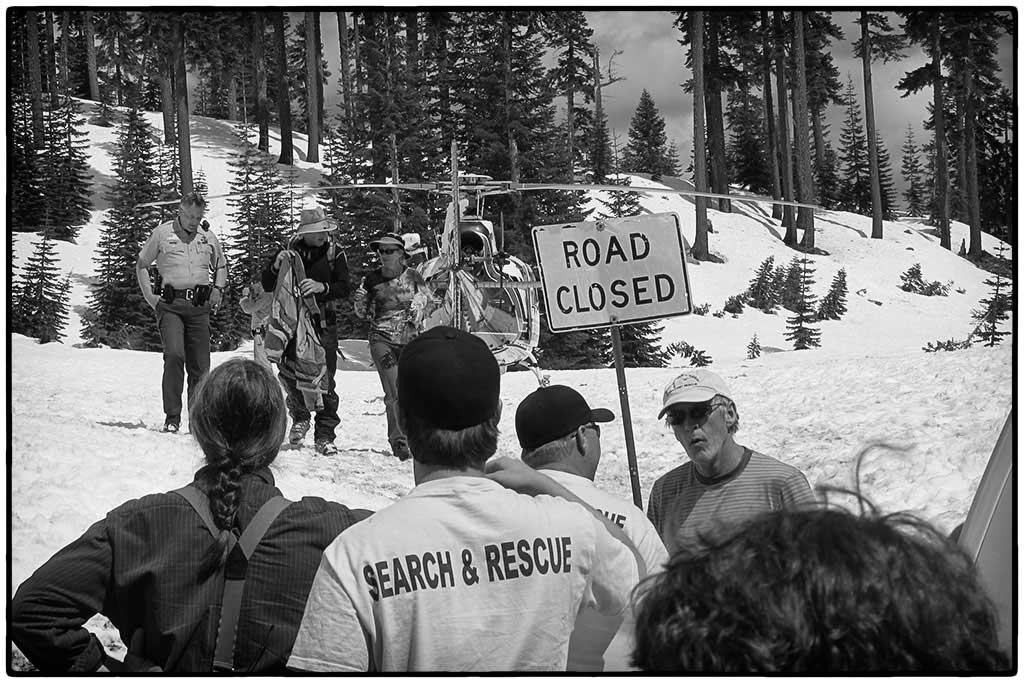

The rangers tasked us with getting him down to Helen Lake, the highest they could arrange for a helicopter pickup. We were concerned, however, about his ability to get down safely. He was exhausted, stumbling his way down the mountain. Below the summit pinnacle, crossing the plateau and heading down Misery Hill, we were negotiating relatively safe terrain. But approaching the steep slope down to Helen Lake, we were concerned. If Lonnie were to slip, he did not look like he would be remotely ready to self-arrest. Thankfully, we found a short-roped guided party descending just above Red Banks, and asked the guide for assistance. He roped up with Lonnie and kept a close eye on him. Confident that Lonnie was under watchful eyes, we skied down to Helen Lake, and waited for Lonnie to get picked up by the California Highway Patrol helicopter. We packed up and left, skiing all the way back down to the parking lot, desperately skating the last flattening mile, running out of forward momentum only a stone’s throw from the parking lot. We were greeted by a full on search and rescue hubbub, with volunteers, rangers, and sheriffs abound. We managed to find Lonnie’s waiting family and assure them he was okay.

It was an emotional scene as Lonnie’s chopper landed and he was met by his wife and children. It had been hours since we had found him on the summit, and he was really at the end of his rope, but he still recognized us and thanked us for our help. We had simply been in the right place at the right time, but we had also been prepared.

Now, if this were the 1930s and I was a journalist looking for a story to sell, or even if it were the 21st century and I simply didn’t know any better, I might have claimed that Lonnie was a Lemurian. His supposed disappearance? Just an act. To what end, one can only speculate, but the rescue helicopters buzzing the mountain on busy spring weekends must be of particular interest to the Lemurians, given their historical propensity for airship construction. Beyond that, I say it simply makes more sense. What else are all the Lemurians up to? Where else could they be hiding? Lemurians inhabit Mount Shasta, and I inexplicably encountered Lonnie on the summit of Shasta, so therefore Lonnie was a Lemurian. Quod erat demonstrandum. Add it to the rolls of Lemurian lore. What’s that you say about affirming the consequences? Logical fallacies be damned! I have all the proof I need. Now, if only I could remember where I left my magic root beer crystals…

There must be some meaning here, in the readiness of men to attribute the otherwise inexplicable to something discrete, if abstract and totally fictional. Where did this mountain come from? What could be the cause of the strange reddish-green glow on Shasta’s summit at dawn? How could a man leave his wife at high camp and make a summit attempt alone in worsening weather, without emergency supplies or extra clothing? (I am sure it seemed like a good idea at the time. I do not wish to judge; bad things can happen in the mountains.)

In lieu of any concrete answers, I suppose Lemurians fill the void just as well as anything.

Regardless, these things are clearly not for us to understand. The mysterious ways of the Lemurian wise men are far beyond this realm of comprehension. As long as I could plumb the depths of such mysteries of Mount Shasta, I have learned that the mountain itself is merely a signpost, directing us towards greater questions at hand. In the wise words of our gal pal, Ashalyn, “Galacticism is the art of understanding one’s galactic heritage and now is the time for us to do just that.” Back in this galaxy, where pursuits such as skiing, fishing, and climbing are of the utmost spiritual inheritance, Mount Shasta has its own particular prominence.

Shasta makes an excellent introduction for the aspiring mountaineer. I had some misgivings the first time I discussed a plan to climb up and ski down the mountain with my backcountry buddy, Chris. So, what route should we do? “The most straightforward one,” Chrix led me on. Oh yeah, what’s that one? “Avalanche Gulch.” Avalanche Gulch? I admit, it sounds pretty ominous. But in all seriousness, Avalanche Gulch is one of the best introductions to mountaineering I can imagine.

To call it a trade route is an understatement; for better or for worse, it is a superhighway up the mountain. On a popular weekend in the prime season of late spring and early summer, you might be accompanied by several hundred other climbers, many probably from the Bay Area, eager to conquer their own backyard mini-Everest. The route receives so much traffic that there are U.S. Forest Service climbing rangers posted at the 10,400-foot high camp at Helen Lake. There are designated urination stations, and the Forest Service has a standardized poop-packing procedure for which they distribute supplies. This includes a handy foldout bullseye to zero in your targeting, not to mention a bag of kitty litter.

The Avalanche Gulch route requires zero glacier travel, zero ropes, and zero technical climbing skills. What it does require is the ability to wield an ice axe and crampons to safely ascend steep slopes and self-arrest in case you fall and start sliding uncontrollably. The ability to confidently self-arrest is an absolutely necessary skill, but nothing that a couple of hours of practice cannot prepare you for. For us, the high camp at Helen Lake was a perfect place to practice these skills in the afternoon hours, for the approach to Helen Lake is not steep enough to require them.

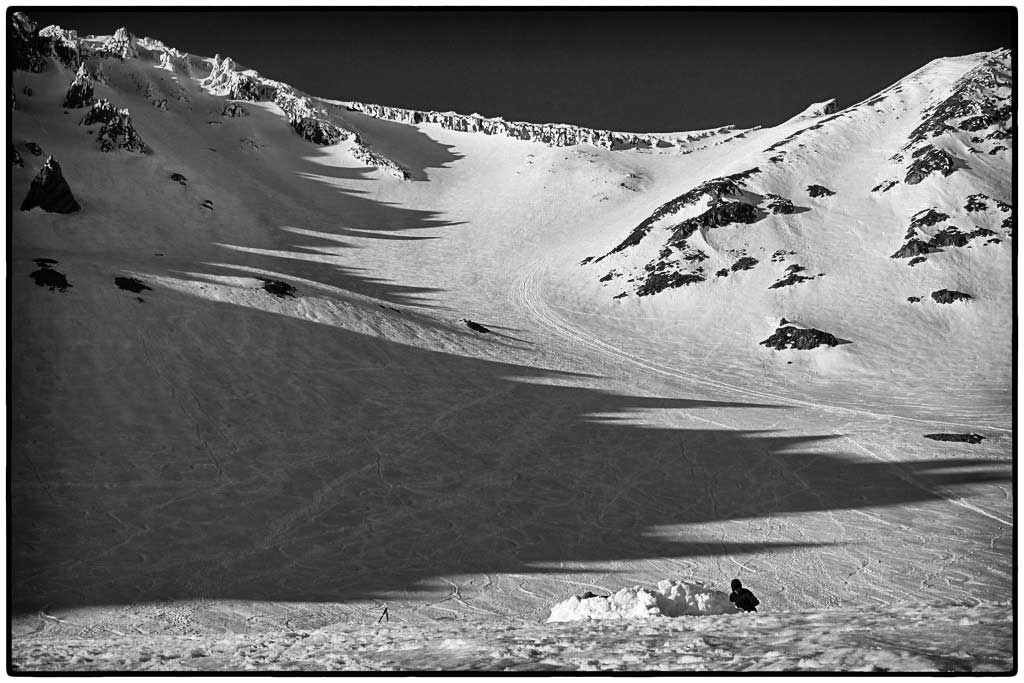

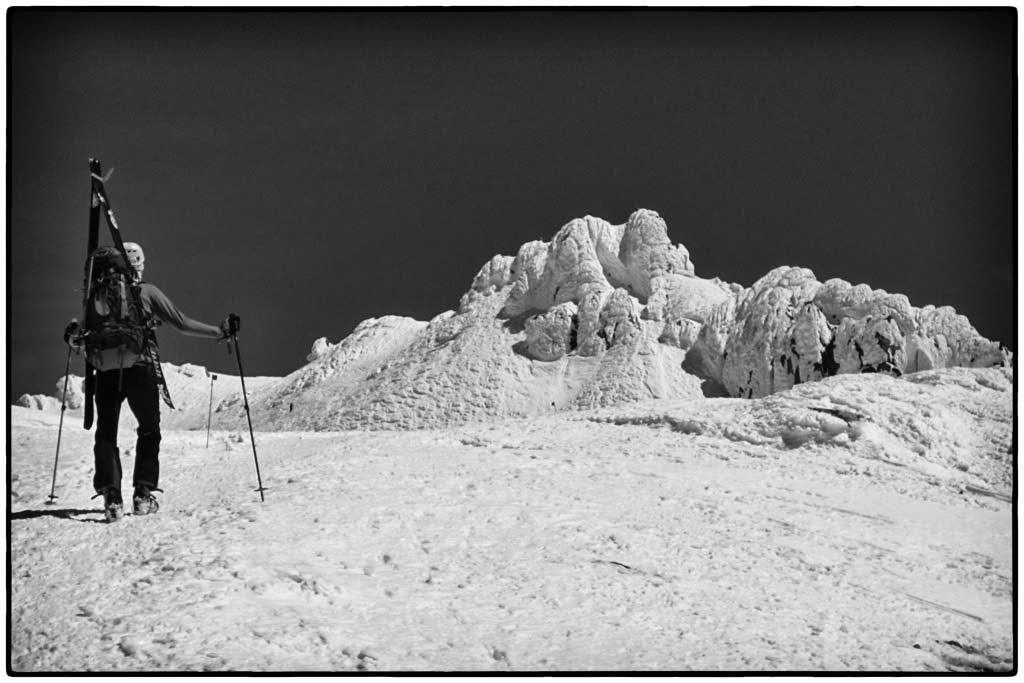

This year, it took us exactly four hours on skins to ascend from the Bunny Flat trailhead to Helen Lake. We set up camp, lounged around in the sun, built a snow castle, drank whiskey, and went to bed. Most of the climbers get a super early alpine start but this year we decided to sleep in, in order to let the corn snow get a head start on buttering up. We aimed to time our descent afternoon. We departed Helen Lake after 7 am with boots and crampons and reached the summit plateau sometime before noon. With incredible weather, all sun, and zero wind, we took the opportunity to explore around the summit, peek at the north and eastern faces, and eat lunch on the summit plateau.

Whilst lazing about in the sun at 14,000 feet, we encountered a guided party that had ascended Casaval Ridge and was getting ready to descend. One particularly excited snowboarder was assembling his split board when one of the halves slipped away from him. It began to slide down the very gradual descent of the summit plateau. We all watched as the events proceeded in slow motion, the board beginning to gather speed down towards Misery Hill. There was one lone climber on the far side of the plateau. The guide shouted and waved his arms, in a desperate attempt to grab his attention and stop the runaway board. The good Samaritan made a lunge with his pole and jabbed it, flipping it on its side. The owner of the split board turned around and pumped his fist with joy, relieved at his apparent good fortune. But all I could do was stare and mutter, “uh…. it’s still going.” The board managed to maintain momentum, righted itself, took a hard left turn, and sailed off the edge of the summit plateau, down the Konwakiton glacier, into oblivion. Goodbye, split board.

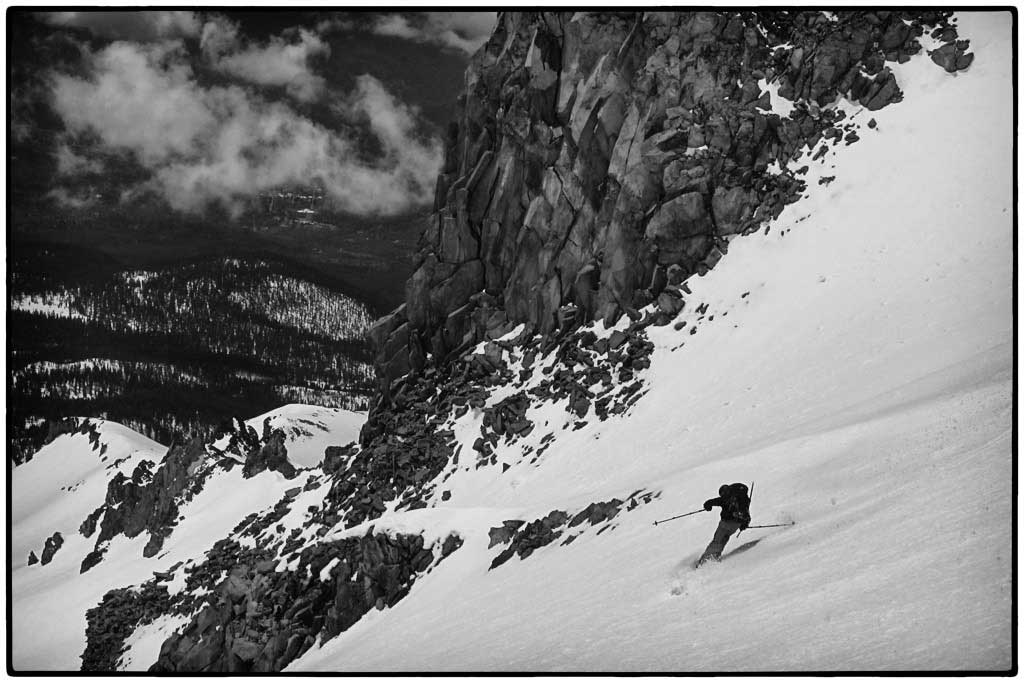

By that time, we were getting light-headed from the altitude on the summit and decided it was time to ski the Trinity Chutes. Some of the upper portions of the snow on Misery Hill were still bullet-proof rime ice, but there was great chalky snow on the upper Konwonkiton, before cutting across with a short walk to the top of the Trinity Chutes. The line was absolutely pristine, perfect, incredible, and unforgettable. Skiing in the shadow of massive rime-covered red rocks down 45-degree chutes on velvety corn is the type of thing I could do for the rest of my life.

And come to think of it, why shouldn’t I?

Well, a mountaineering accident this past summer left me with a severe concussion, a broken hand, busted skis, memory loss, thousands of dollars in medical bills, and friends questioning the responsibility of my bolder pursuits. And you know what? Their concerns are valid. But when I go back to those places and recount the misadventures, the near misses and the direct hits, the stories to tell, the life lessons learned and the ones forgotten, the moments of struggle and revelation, still all I can think is… where are all the damn Lemurians?

Wait, what? Sorry, that’s not what I meant. I think that’s the concussion talking. That story will have to come later. What I meant to say was, why shouldn’t I follow this path?

Of all the unanswered questions that Mount Shasta has left with me, that one is the most mysterious.