There and Back Again: Ode to Tahoe

At San Jose Hood Cleaning, we love coming across great blogs and articles that we think should live on. So we brought this site back for those who love mountain stories.

Seasons are changing again. Spring has sprung, the snow has stopped falling, and the ski lifts have stopped running. So, time to go fishing? Well, not so fast. Tahoe resorts have closed, and I suppose they have their reasons, but spring skiing is good as long as the snow sticks around. Spring is an encore; snowpack and weather stabilize, opening up access to longer routes and more difficult peaks. A daily melt-freeze cycle sets in, with temperatures staying cold enough at night to refreeze the water between grains of snow that melted during the day. As the coarse frozen snow bathes in the arrival of the morning sun, the bonds melt again. This is corn snow, creamy velvety butter, a harvest almost as prized as a fresh powder for the downhill enthusiast. But only if you can time it just right.

Unfortunately, overnight temperatures have stayed too high and the sun has returned with gusto this year. Tahoe’s snowpack simply hasn’t accumulated deep enough to withstand the sun’s radiating gaze as long as usual. Where only weeks ago there were great expanses of blinding snow, the earth now lies stripped of its veneer. Winter is officially over. What little snow is left has been eroded by exposure and sullied by dirt. It’s not like last year when we skied fresh powder in May and June, and resorts stayed open until July. No, the season for spring skiing and corn harvesting in Tahoe is ending fast.

Yet still, I drive up. This journey has happened so many times, the rhythms are intuitive. We will wait, biding our time until the people return to their families and traffic dies, clearing our way. Only then do we embark, thieves in the night, smugglers stealing away across empty roads under the cover of darkness and falling snow. We clear the confines of the city and hit light speed, spots of snow stretching into streaks of stars, dense fog and dust drifting in space, blurring our vision, leaning forward in the cockpit with strained eyes, flying blind into the night.

The drive is full of exhilaration, anticipation, and monotony. The hours add up and so do the gallons. I find people and ways to share the costs when I can. But sometimes you find yourself alone. And so I go, alone. This is what I live for. Within the bounds of this job, and the confines of this lifestyle, I know no other viable options. The alternatives require a drastic change of circumstances and scenery. I make my plans, but in the meantime, I settle for routine escapism. This is how I maintain some semblance of sanity. This is what it takes. This is the way of the weekend warrior.

The transition begins as you gain elevation. Adrenaline accelerates through blood, and the car speeds across buried lines on the road. I arrive in the black of the night to a different time and place, filled with the presence of emptiness: of displaced children and families, long since priced out of the neighborhood; legacies of polyester suits, cheap motels, and neon lounges, long since shuttered; sweet scents at dusk of fire and ashes, long since dissipated; loose chains kicking up road salt onto a car in an icy ditch, long since abandoned; the vast woods looming silently aware, long since indifferent; a lone traveler passing through, long since gone.

Neurons fire as the night subsumes me, waves of history and legacy washing chemicals across my mind’s eye, developing negatives, projecting positives. Worlds within worlds lurk beneath the surface of Tahoe. Memories of the season come flooding in, through open doors, and a new place welcomes me home. I am connected to a new world. My old one becomes harder and harder to return to. I feel like I belong here. Giddy with anticipation, I lay myself down and relive recent ramblings with glimpses of what might fill the world tomorrow.

It is the biggest week of the year. By one count, there is 99″ of snow in seven days. This week in March accounts for almost a third of the season’s total snowfall. I find myself out in the thick of it, joining the Tahoe Backcountry Ski Patrol as a ski-along, a recruit. I learned about this volunteer-based group through a friend of a friend of a friend back on opening day. The notion of a “backcountry ski patrol” initially gives me pause. It seems an oxymoron; the backcountry by definition exists out-of-bounds, beyond the reach of any resort, of any typical ski patroller.

But this organization serves an important purpose. Partnering with the National Ski Patrol and U.S. Forest Service to look after popular winter backcountry areas on the weekends, the patrollers offer information and assistance to backcountry travelers. The patrollers themselves gain valuable training and experience from regular patrols and participation in Search and Rescue. They also take the to opportunity gather data on winter trailhead usage, helping the Forest Service pad its budget. It is a symbiotic relationship.

I meet up with five patrollers at the Castle Peak area north of Donner Pass and we head down the trail. The patrollers are genuine and amiable people, which is particularly useful when it comes to public outreach. Our leader, Bill, has a contagious enthusiasm balanced by a sober aura of expertise. Most of the recreationists we meet are friendly and eager to talk. They ask about what we do and we share our observations and knowledge of conditions. The patrollers play an interesting role, one of public service, but without authority. Any member of the public is free to disregard their input. And some do. It is a free backcountry, after all.

Still, I am taken aback by some of the people we encounter in the woods. It has stopped snowing this morning, but three feet of fresh snow have fallen in the past twenty-four hours. The avalanche danger is high on all slopes and aspects. Venturing out on days like this requires some understanding of the risks. But the people we encounter don’t act like they recognize what they might be getting into.

We encounter a lone snowboarder heading out of the blanketed woods, wearing an overnight-sized pack, a mop of blonde hair, and a wet cotton hoodie. He says nothing as we pass. Did he really spend the night out, I wonder, dressed like that? Only a quarter-mile later we find a single snowshoe lying abandoned in the middle of the trail. There are tracks going in both directions. Did it belong to the snowboarder? We continue down the trail, overtaking a group of middle-aged women. One is wearing low-cut tennis shoes with plastic grocery bags tied around her feet, strapped into her snowshoes. Except, one foot is missing a snowshoe. And this woman hasn’t even noticed.

We offer some polite advice on proper footwear and she laughs it off. “No money for waterproof boots”, she says, “I’m saving up for a new tent”. Someone goes back to fetch her snowshoe. We continue, ascending Andesite Ridge towards the Sierra Club’s Peter Grubb Hut, our destination for the day. As we ascend, the clear path stops, and we begin to break trail. The snow is deep, very deep. Clearing a path for others to follow is exhausting. The patrollers rotate shifts in pole position and we proceed up the slopes. On top of the ridge, out of the shelter of the trees, the flurry picks up forcefully and visibility begins to break down.

A whiteout envelops us. The wind whips freshly fallen snow, drifts covering tracks as fast as you make them. A mild sense of vertigo and imminent danger sets in. The chilling gusts whisk across my lips and tear a huge grin from my face. I feel alive. The slopes are unstable and we stick to the ridge lines. I deploy the handle on my airbag, just in case, which does not go unnoticed by our fearless leader, Bill. Simple ski cuts and stomps trigger small surface slides on the least steep and dangerous portion in front of us. One patroller in particular is clearly alarmed at the rapidly developing conditions. We need to turn around. Where are our tracks? It is not safe here. The plan is revisited and new options are evaluated. We do not ski down. Our party prepares to turn around, to skin down the very same ridge route we ascended.

Incredibly, we are not alone. Two skiers emerge from the howling white void and come down the ridge towards us. They intend to ski the same slope we just found to be heavily wind-loaded and extremely unstable. Bill talks to them, sharing our knowledge, attempting to dissuade them of any notion of skiing this slope. Or so I imagine, from hand gestures and head nods, because all I hear is the whistle of a steam engine leaving the station, a blanket of sound. The skiers appear to appreciate our input but signal their intent to ski anyway. There is nothing more we can do.

We tentatively head back down the ridge. Crossing a flat, open section of the ridgeline, I register a hair-raising reverberation, the hollow thud of “whumping”, the sound of snowpack collapsing under my feet. But I never hear anything about those two skiers. We encounter several other parties, most of whom eventually turn back on their own accord, heeding wise words to stay off the slopes. Red flags abound today. I am relieved later that week when there is nobody in the news gone missing near Castle Peak. Maybe those guys didn’t ski that slope. Maybe they did, and they were fine. I’ll never know. But I am not sorry that we didn’t get any turns in. Sometimes the smartest thing is to just trust your instincts and call it, pack up, turn around, and start over tomorrow. It is hard to harbor regrets when tomorrow is a new day.

March and April were the saviors of our 2012 season. I could tell you about the joy the fashionably late snowfall brought to the Tahoe basin, I could show you powdery pillows the size of Buicks and grown men grinning like giddy little boys. But sometimes, just the facts will suffice. If you can read between the lines, numbers can tell a story by themselves. In my day job as a data analyst and business intelligence consultant for big corporations, it is often my duty to sift through the data and find a story to weave words around.

So, here is the season’s headline: it was California’s driest winter in 50+ years. The snowpack in the central Sierra Nevada was at 40% of normal on May 1st. There wasn’t even any permanent snow in Tahoe until January 20th. That is almost unheard of. More than 60% of California is abnormally dry or in a severe drought right now. As far as Tahoe was concerned, the nine feet of snow that fell in March made all the difference in the world. It is almost horrifying to compare this year to last. As of May 9th this year, Tahoe received 322 inches of snow, coming out to about 81% of the average. I feel vindicated in my conviction back in January, sitting at no more than 30% of normal, that it would be unthinkable to finish the year anywhere so low. These things revert to the mean over the course of time. There had to have been loads of snow on the way. But now, at the University of California’s Central Sierra Snow Lab, there are only six inches of snow left on the ground. And this will melt out today. This time last year, there were over nine feet still on the ground, with hundreds of inches more to come.

And yet, for me, there is a more personal story behind the story: despite the relatively dire conditions, I skied more days this year than any other yet. I expect to hit 40 days by the time the snow out West is nothing but runoff. Not terribly impressive by some standards, but not too shabby for this weekend warrior. It’s a little crazy I managed to ski more this year than last, the Great Winter of 2011. But it was last season’s monumental snowfall that reopened my eyes. I have spent too many years in the city. I had forgotten how much I love and live to be in the mountains.

There is just so much here, so many places to explore. It is the first year I am an official member of a group ski lease in Tahoe, having been an irregular guest in years past. We lucked out back in November, scoring a six-month seasonal lease for a beautiful home on Blitzen Road in Christmas Valley, an unincorporated neighborhood on the fringes of South Lake Tahoe. Our house sits one foot out the door down Highway 89 towards our favorite playgrounds around Carson Pass. I look out our backyard directly into the Eldorado National Forest. It is quiet here. My desire to be here all the time, to live here and to work here, grows every day.

My current lifestyle begins to feel unsustainable. The time and expense add up as I make my regular escape to the mountains while simultaneously maintaining this city life. The hours, days, and weeks of my life energy, traded away for dollars and cents, are something I’ll never see again. I truly love San Francisco, but it binds me to this job and I can’t afford it much longer. My fledgling career as a corporate consultant has created close relationships with amazing people and afforded many great opportunities, but there comes a time when you have to be honest with yourself and realign your priorities with your principles. I am following a track that somebody else has set and where it is leading, I don’t care to find out. This is not who I am, this is not what makes me happy, this is not my purpose. I have found where I thrive, and it is not here any longer. Having worked my way up, it is about time to turn around, scope out a new line, enjoy the ride down, and find a new peak to climb.

One of our best days came after the April Fool’s Day storm played a dirty trick on everyone who had given up on the season. The storm snow settled and it was high time to return to the backcountry. Stranded for the weekend, desperately looking for a partner, connections come through for me once again. I get in touch with Brian, our side-country buddy from Kirkwood’s Emigrant Basin, who happens to be planning a ski tour with his girlfriend and a friend named Rusty. But Brian bails at the last minute. “I’m going to evaluate the in-bounds avalanche conditions,” he reports cryptically. Rusty ridicules this rationalization, but I suspect Brian has his reasons; girlfriends can be fickle creatures. I’ve had to pull that move before. Rusty and I have never met, but we connect instantly and meet up to carpool from San Francisco.

We head to the Emerald Bay trailhead early Saturday morning and meet with a couple of Rusty’s friends, including one Swiss fellow, Jurgen, who flew in from Paris the night before. He comes bearing brand new skis and boots, ordered and delivered in the US to avoid the EU’s exorbitant valued added taxes. I am the only one who has skied from this trailhead and I assure everyone the route up Maggie’s is straightforward enough. We hit the trail and Rusty takes off. He competes in triathlons and it shows; he is a trail-breaking machine. We traverse the shoulder between Maggie’s Peaks and ski down the other side. The plan is to head to Dick’s Peak, a long trek, but we maintain the option to stop short and explore the wider area behind Maggie’s. We scope out and work up the nearest peak, lifters engaged, blisters burning all the way. Rusty is hauling straight up the hill; he disappears from sight, leaving only tracks behind.

We reach the top and admire Dick’s in the distance, across one more basin, one more alpine lake. There are a couple of approaches: the straight route from here down and up again, the rocky ridge line from Mt. Tallac, and the long gradual approach from the north. I take pictures for future reference and route-finding, but the snow is cooking too quickly to make Dick’s a prudent choice at this point. The time to ski is now.

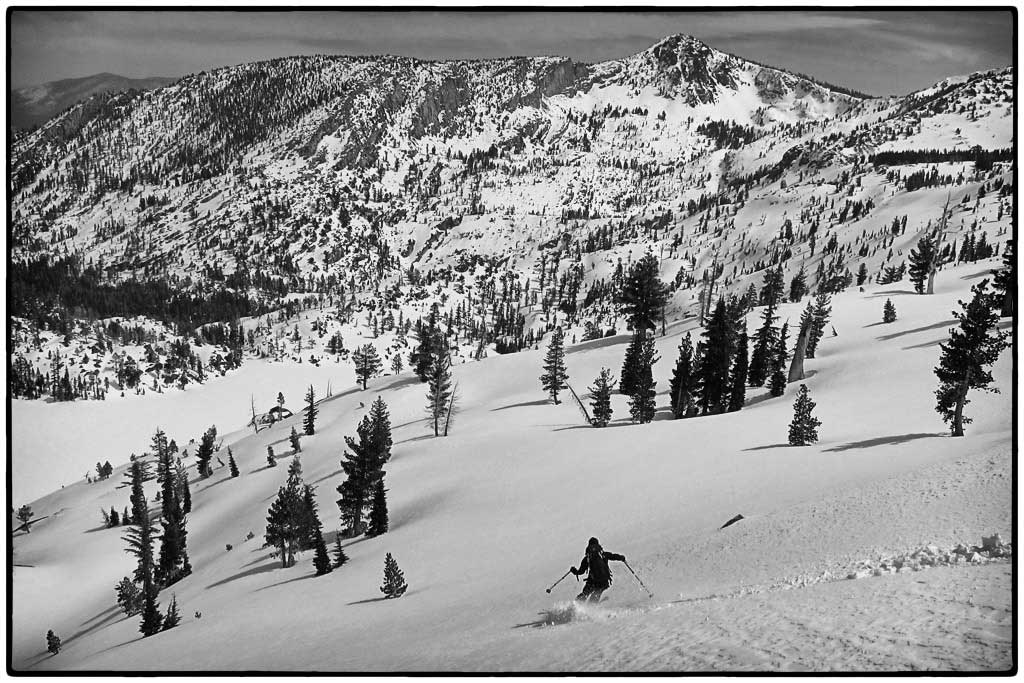

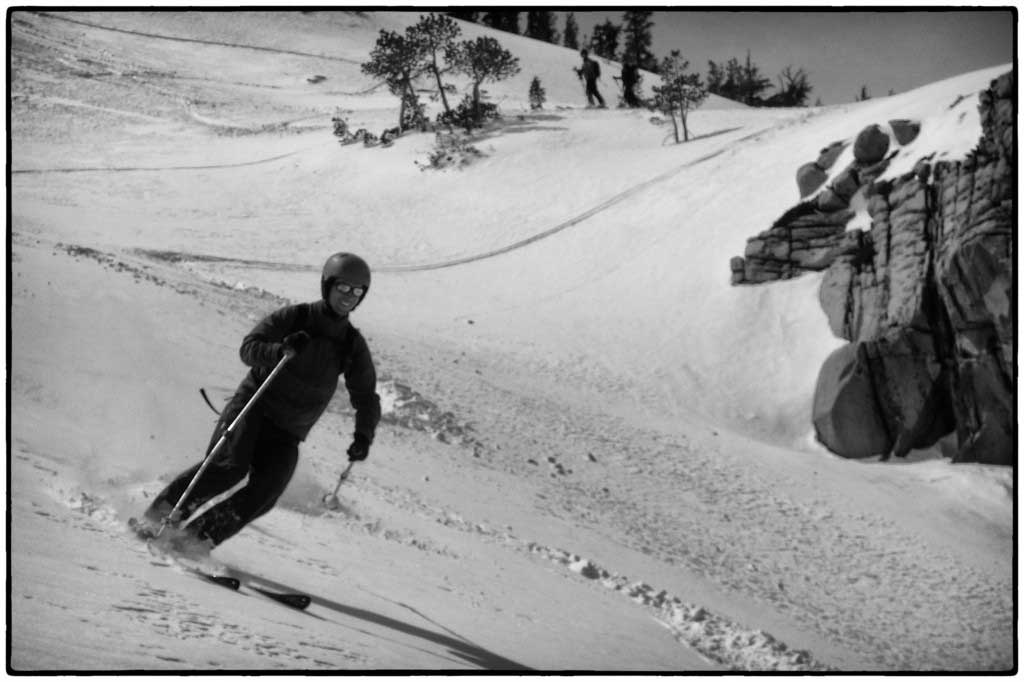

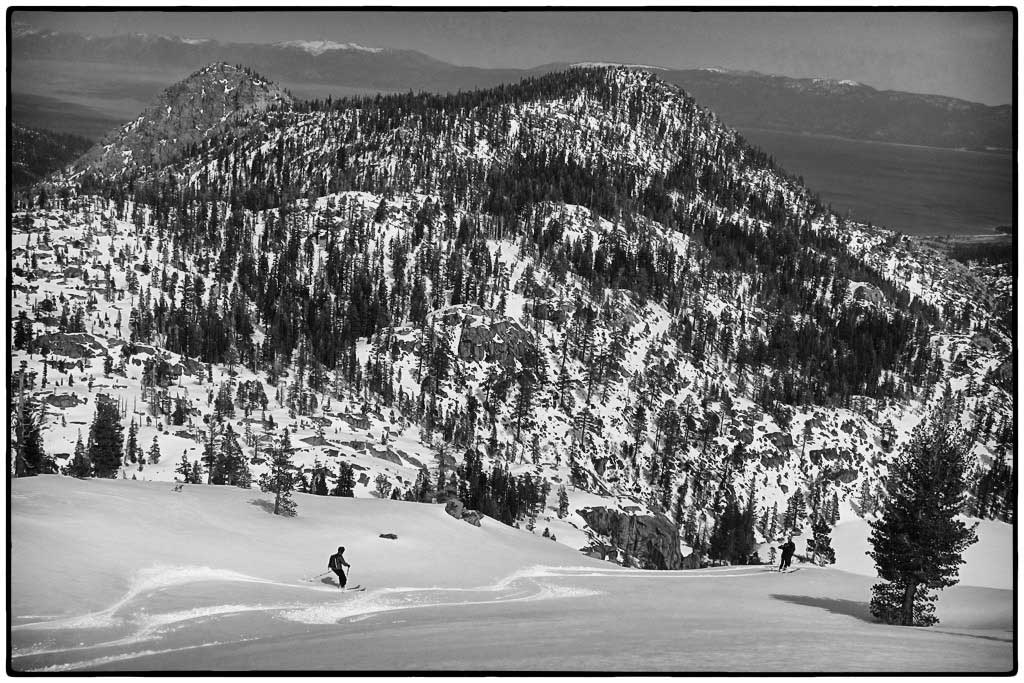

So we drop in, back the way we came. These are the best turns I’ve had all year in the backcountry. The sun is shining, the sky is blue, the lake even bluer, the snow is soft and virgin. Not a single track has been set here since the storm. The avalanche danger, at this window in time, on this aspect and this slope, is almost nil. We haven’t a worry in the world. We hoot and holler, ripping turns down the eastern face of this unnamed peak above Azure Lake. The view of Maggie’s Peaks framed by Lake Tahoe and the east shore of Nevada is stunning. Rusty’s shit-eating grin is contagious. There is nowhere else in the world I would rather be.

Pausing for breath, absorbing the view, I reflect on the lay of the land around us. This is the Desolation Wilderness. Named for the barren, rocky basins and gnarly old-growth conifers, you might suspect it to be a dark and foreboding place. Nothing could be further from the truth. While deserted, it is not dreary; while lifeless on the surface, it is far from lonesome. We are so far removed today from any and all things desolate, I suppose this ought to be the Jubilation Wilderness. The nearby hills have all been designated on a very casual first-name basis: Dick’s Peak, Jake’s Peak, and Maggie’s Peaks. All are named after local settlers. But it is only this one particular pair of peaks in front of us, a couple of buxom bumps, that is named after a woman. I am reminded of Wyoming’s highly suggestive “Grand Tetons”. You just know what these sex-starved settlers had on their minds.

I admire the view of our tracks behind one last time as my first alarm goes off. Waking with a smile as dreams of the season fade from my mind, it dawns on me that it is our last ski weekend in Tahoe. It is 6:30 am and from my bedroom window, I can already see the sun beating down on the easternmost flank of the Desolation. Forget spring, it’s going to be a summer day today. To cap it off, we’ll do what we’ve done all season when the sun is bright and the snow is low: head down the road to Carson Pass. It is time to pay one last ceremonial visit to our old friend, Round Top.

The history books will say that this was a forgettable year for skiing, but honestly, the statistics mean nothing to me. This life is only what you make of it. I know this season will live in my memory forever. My eyes have opened to new possibilities. This weekend warrior is going to downshift and find a way to live the dream. People do this. They do it all the time. They find ways to make it work. This is how it begins.

Thank you for an epic season, Tahoe. But don’t worry, I’ll be back soon. We have rivers to fish, crags to climb, and unfinished business to attend to.